skip to main |

skip to sidebar

********************************************************************************************************

******************************************************************************************************************

*********************************************************************************************************

.jpg)

**********************************************************************************************************

The film tells a familiar story — crusty oldster finds humanity through a needy child — in bracingly unsentimental fashion. Brazilian-legend actress, Fernanda Montenegro, plays Dora, a bitter retired schoolteacher who earns money by writing letters for illiterate patrons in a Rio train station. The fact that she never bothers to mail the letters is a function of her chilly disregard for the human race.

The agent of her redemption is a little boy named Josue, played with miraculous emotional honesty by Vinicius de Oliveira, whom director Walter Salles found shining shoes in a Brazilian train station.

After his mother is killed, Josue badgers Dora into taking him to find his father in a distant province — but only after she has very nearly abandoned him to an unknown fate in a city where youthful thieves are gunned down by private security guards. Their trip together is an ordeal and an adventure, punctuated by Dora’s efforts to unload the boy. But the boy refuses to let her run away.

Together they encounter outlaws, pilgrims, and a kind-hearted Christian truck driver who seems, briefly, to be Dora’s savior. Eventually, they find their way to something like home, in the heart of a remote world neither entirely understands.

All the same, the film is affecting and pointedly unsentimental in its portrayal of the often grudging relationship between the gruff, callused Dora and Josue, who only abstractly grasps the importance of the search they've undertaken and doesn’t realize, as the audience does, that its result will determine whether he will join the ranks of the country’s millions of street kids or manage to get a shot in life through a family connection.

While the duo never find Josue’s father (whom Dora keeps referring to as a drunkard and abuser), they eventually do find his two half-brothers, idealistic young men who ultimately end up raising the young boy. They also discover that Josue’s mother was really the love of his father’s life and that he had traveled to Rio to find her - not the bad man Dora had painted after all. The final image (and natural conclusion) is a heartbreaker, yet we know these two people we’ve come to know so well, have ended up so much better than they had begun.

I wasn’t in the mood for this film, but it got to me anyway. The main reason is Montenegro, who is kind of a Latin Jessica Tandy. The film kicks in hard at the point where Dora is broke and suddenly very desperate. The hook here is the letters she writes for others. As people read or dictate them, they reveal themselves. Even when, late in the movie Dora reads aloud from someone else’s letter, she reveals her own feelings. The letters accentuate a theme of loneliness and the inability to communicate. Dora survives by helping others speak, but fails to deliver the message. She redeems herself by attempting to personally deliver the letter and the boy to his father. On the way, she crosses both physical and spiritual landscapes to reach others. The letter, child, and now spiritual mother complete the journey by meeting another letter. Dora then writes her own to mark her return from one frontier to leave her heart at the other end.

Long one of Brazil’s leading stage and screen actresses, Montenegro carries the film superbly with her portrait of gritty strength being worn down to a state of tattered vulnerability, while newcomer de Oliveira, a shoeshine boy who won the role over 1,500 other aspirants, is engagingly natural and happily doesn’t beg for viewer sympathy. Director Walter Salles presents the side of Rio which most tourists don't see - it's ugly, painted in sallow colors, crowded and harsh - certainly no place for young children (a teenage thief is shot on the train tracks for stealing a cheap radio from a junky subway stall). When we meet Dora, she seems a natural part of this unlovely landscape. She's not pretty, either physically or spiritually, her only wish being to make enough money for her petty trifles like cheap booze. Montenegra is perfect in this role and was Oscar-nominated for Best Actress in 1998. While she did not win, I thought she should have.

On a precise but restrained symbolic level, Central Station speaks cautiously in a hopeful manner about the possibilities for Brazil’s future. It suggesting that the deep scars left by the social ills of the recent past might somehow be survived and surmounted by a creative union of the old and the new Brazils.

***********************************************************************************************************

The film is constructed from three distinct stories linked by a car accident that brings the characters briefly together. Octavio is sharing an apartment with his brother, which leads to a serious problem when he falls in love with Susanna, his sister-in-law. Octavio and Susanna want to run away together, but Octavio has no money. He does, however, know a man who stages dog fights, and he volunteers his dog Cofi for the next round of fights. Cofi bravely rises to the occasion, but the dog's success in the ring leads to a violent altercation. Elsewhere, Daniel, a successful publishing magnate, leaves his family to take up with a beautiful model, Valeria. Valeria, however, soon loses a leg in an auto accident, and as Daniel tends to her needs, her tiny pet dog gets trapped under the floorboards of their apartment. And finally, El Chivo is an elderly homeless man who is trying to contact his daughter, whom he hasn't seen in years. Desperate for money, El Chivo is hired by a businessman to assassinate his partner; however, as he's following his target, he’s interrupted by an auto accident, from which Octavio and his injured dog stagger in search of help.

Translated very loosely as Love’s a Bitch, a phrase that’s invoked both literally and figuratively, Amores Perros opens with a spectacularly jarring car crash and flips back and forth to show how the victims and onlookers collided at the scene.

What a shock, then, to see Amores Perros and discover that Mexico City is actually... a hotbed of violence and vice! Boasting the highest canine mortality rate since Verhoeven’s Hollow Man, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s thriller opens with a cautionary note that no animals were harmed in the movie’s making--no doubt to allay fears that life is cheap south of the border. But violence against animals on film seems a lot more shocking and taboo than violence against humans—an issue this trio of intertwined stories exploits to disturbing and frequently dazzling effect.

And all of that makes it sound pretty depressing as well, so let me digress by saying that the film takes a lot of fun and energy in telling its stories without losing the edge. Indeed, some of the best moments in the film play like the soap operas where Selma Hayek received her start. Every character has a love lost or a love to strive for. Love is a bitch, the filmmaker’s tell us, but it is also a force that can drive people beyond things like dreams and plans. “Plans are what we tell God, so He can have a good laugh,” one character says at a pivotal moment. Now, isn’t that an absurdly tragic line. And Amores Perros is one of those few films that can exist in all the different worlds of these characters, tragic and absurd.

The movie bears more than a passing resemblance to Pulp Fiction. It has three major stories, each of them beginning with a title card. The stories weave and wind through each other without adhering strictly to straightforward chronology. The feel of the movie is gritty, at times suspenseful, at times frantic, and often violent and bloody. Its subjects are low lives, people who would do terrible things for money and love, or people who do terrible things with the money they have. What it doesn't have that Pulp Fiction does is the humor that made Pulp Fiction's proceedings feel like a black comedy. Amores Perros is all serious, always observing the human condition with a sad, pitying eye.

I pretty much hated this film! It was way too long of a feature to watch in a classroom, and it was way too graphic for me to watch. I’m a dog lover myself, and I cannot stand watching scenes of dogs killing each other for the pleasure of humans, who mistreat their dogs and use dog fighting as a fun sport. There were a lot of scenes in which the dogs were fighting and actually show the violence of the sport. I even looked away from the screen a couple of times, but that was worse! Because all I heard was the growling and yelping of the dogs! In the second story, about the crippled model, I was feeling even sorrier for the dog, which fell into the hole of the apartment floor. Throughout that entire story line, the dog was stuck under the floor of the apartment, which was full of rats. I also couldn’t stand the sight of the scene where the dog fighter killed all of the dogs and puppies in the assassin’s home. One positive note about this film: If you are a dog lover, this film will make you love your dog even more and feel sorry for all the house dogs and stray dogs, who could be victims of a vicious dog fighting ring (Talking to you, Michael Vick!)

*****************************************************************************************************************

The film is centered on events, particularly during the period from December 1992 to January 1993 in India, and the controversy surrounding the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. Increased religious tensions in the city of Bombay (now Mumbai) led to the Bombay Riots.

Bombay ends on a hopeful note, but not before etching a series of wrenching images in the minds of viewers. Director Mani Rathnam has shown great courage in making this picture (bombs were thrown at his house after it opened in India), which speaks with a voice that many will not wish to hear. Bombay recalls how forceful a motion picture can be. It also reminds us of the maxim that those who don't learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Hopefully, some day, humankind will understand the lesson that Rathnam is teaching here.

Another thing we are shown, and this is quite a common message in the Indian cinema lately, is how the riots are the result of the politicians’/religious leaders’ vicious manipulation of the people's minds. Although the political message of the film is very plain, to the point of being of pamphlet quality, and the emotional dirty tricks are felt as so many blows below the belt, it takes Bollywood to make from all this tricky material a gripping story that has the audience watching on, with a lump on their throat, for three hours.

You can also find more levels than just the purely superficial in the movie: there is always the symbolism, so dearly loved by Indian cinema, as in the case of the twins and their fate. And there are some subtler messages: when one of the boys gets lost and is in danger of being trampled to death by a terrified mob, he is rescued by a eunuch. And it is this most despised and marginal of members of society who, while tending to the boy’s wounds and feeding him, finally explains to the boy what religion is, and what is the difference between a Muslim and a Hindu.

Mani Rathnam shows how Bombay struggles to find a narrative that can reconcile communal differences. She looks in detail at the way official censors tried to change the film under the influence of powerful figures in both the Muslim and the Hindu communities. In going on to analyze the aesthetics of Bombay, she shows how themes of social and gender difference are rendered through performance, choreography, song and cinematography.

Within film and television or within modern novels and books have had various star-crossed lovers labeled as notable and “unforgettable” love stories. Obviously, the greatest star-crossed lovers’ story ever told is William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the play that has become a popular icon, in terms of forbidden love stories, and inspired a movie like Bombay into a beautiful story about love. I consider Buffy Summers and Angel from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to be one of the genre’s most tragic and notable star-crossed pairings. Other examples like, Cole Turner and Phoebe Halliwell from Charmed, Nikita and Marco from La Femme Nikita, Kara Thrace and Lee Adama from Battlestar Galactica, and Clark Kent and Lana Lang from Smallville are other star-crossed couples from that particular genre. More star-crossed, couples such as, Jack Dawson and Rose DeWitt Bukater from Titanic, Landon Carter and Jamie Sullivan from A Walk to Remember, Anakin Skywalker and Padmé Amidala from the Star Wars saga, and Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist from Brokeback Mountain. Also, more recently, Bella Swanson and Edward Cullen from Twilight and New Moon, and Jake and Neytiri from Avatar have been included.

The biggest significance of this film is the music and musical numbers. The original soundtrack features the music score and six songs from the movie are composed by A. R. Rahman, with lyrics in the Tamil language by Vairamuthu. The soundtrack was also dubbed into Hindi and Telegu. You would know Rahman as the composer who won two Oscars for composing the music and songs from the 2009 Academy Award winning-film, Slumdog Millionaire. As usual with Bollywood films, there are musical numbers, but in this case we don’t have any major star of India, although the main actors are great (Manisha Koirala is especially charming in the style of Audrey Hepburn); but you have to watch out for the support actors: whenever the two fathers-in-law (one of them a very pious Muslim, the other a very pious Hindu...always having comical clashes) are in a scene the screen rocks! This film is not your average everyday American Broadway musical! The music and the songs were very catchy, fun to listen to, but you could easily tell that the actors in the movie were lip-syncing the songs through every single number.

Though Bombay may not tick your intellectual brain... It surely engages your heart into an emotional journey. Mani Ratnam is really successful at bringing in the perfect Indian middle-class life with stunning cinematography and flawless acting. For those you want to see a nice movie filled with a good story line, not heavy on emotion and above all a scintillating music this is a good movie to see.

********************************************************************************************************************

This film tells the story of a semi-retired and widowed Chinese master-chef Chu (Sihung Lung) and his family living in modern day Taipei, Taiwan. At the start of the film, he lives with his three attractive daughters, all of whom are unattached. The three daughters are: oldest sister Jia-Jen (Kuei-Mei Yang), still nursing wounds from a love that evaporated long ago, now teaching school to a rowdy roomful of horny adolescent boys. Middle sibling Jia-Chien (Chien-lien Wu) has made herself a successful career in an airline corporation, though she might have preferred the culinary arts her father so magically practices. Finally, Jia-Ning (Yu-Wen Wang), who comes up with tuition money by working at a Wendy’s in Taipei; she just wants to get by and get along with everyone, at least until she becomes attracted to the lonesome boyfriend of her fickle, teasing coworker.

Eat Drink Man Woman, derived from an original script by James Schamus, Hui-Ling Wang, and the film's director, Ang Lee, is simple, light, and hard to hold anything against. The main character, Mr. Chu (Sihung Lung), is a consummate chef whose sense of taste has begun to dull as he enters old age. Also growing less secure are his relationships to his three, very different daughters—as though three sisters in the same movie ever have anything in common. In fact, part of what gives Eat Drink Man Woman its appeal, at least for an American viewer like myself, is that the unfamiliar pleasures of the scrumptious fine food and the Taipei setting are comfortably nestled within a tried-and-true, instantly recognizable plotline. A major theme of the movie is that romantic relationships give life meaning and are necessities of life (such as eating and drinking).

This film is set in Taipei, and is spoken in Mandarin. The important theme to this story is hinted at when the father repeats to his daughters that he has lost his taste a long time ago. The audience later knows that he was referring more to his taste for life rather than his physical inability to distinguish flavors. This lack of appreciation for life comes with age as well as his loneliness from accepting the inevitable -- that his daughters are going to leave him alone someday. There are so many subtleties this film is able to capture about not only the Chinese culture, but living with women in general. Each daughter's relationship reflects the uniqueness of individuals. Eat Drink Man Woman is full of humor, wisdom, and grace.

I love to watch this film. I suggest that you eat a full meal before you watch this motion picture. The savory dishes created by the father who is a chef in a major hotel in Taipei, Taiwan makes your mouth water and your glands salivate. I want to be in this film and enjoy a meal with the master chef. Ang Lee is a superb director who has captured family dynamics in modern day China. Whether you are a China expert or just starting to learn about the culture, this is a great way to experience the internal life of an atypical Chinese family. The story will captivate you; the ending will be a surprise to you. This film is definitely more of a chick flick than anything else. It's like a Taiwanese Sex and the City, even with the use of the theme music from the film/television show. This is truly a movie with an ensemble cast. There are four different stories that surround each of the four main characters. This film has comedy, drama, and romance (That's why this movie is a chick flick!) For everybody and for me, especially because I am a good cook and love food, there was the constant gourmet dishes being cooked, served, and consumed!

****************************************************************************************************************

Some of the greatest French movies have been remade for US audiences and no one knows about it. French Director Luc Besson made one of his best with this movie. Because I don’t speak French, it is better for me to watch subtitles than listen to terrible English dubbing. Fans of the Bourne series will probably enjoy this film. After the first 20 minutes, I thought the film was kind of boring. I had no idea where the plot was going, but soon after, La Femme Nikita began to pick up pace and developed into a film I really enjoyed. The movie creates an interesting dialog between violence and the woman's growing reaction to the violence she has to commit. An interesting love twist further develops the character and that’s what the movie is about.

More importantly, and as some reviewers have noted, Nikita combines thrilling action and tension (without the expensive FX) with a very touching sense of humanity. Here you have a junkie social reject turned into a proper, well-behaved, yet deadly government agent. It’s interesting how the government selected someone who was about to go to jail, rather than picking from a horde of eager, patriotic young recruits who would beg to do the job. The government’s mistake is that they assume this reject is just effectively a machine and has no redeeming human qualities. As the film progresses, you see that Nikita yearns for intimacy and love - it's what makes her vulnerable and it's also probably what makes her so good at the job.

A gang of junkies breaks into a drugstore, but the police arrive and corner them in. All are killed, with the exception of a young woman (Anne Parillaud). She is arrested and immediately sentenced to death. Before the sentence is carried out, however, the government gives the woman a second chance – they promise to let her live if she agrees to work for them. She does and her death is faked. The woman is instantly locked in a secret facility where she is trained to become an assassin. Three years later, the woman is released with a new identity - Nikita. She is told that when the government needs her services someone will contact her. A charming store clerk, Marco (Jean-Hugues Anglade), falls for Nikita. The two become friends and then lovers. Nikita likes her new life and decides that Marco should never be told about her past. Then, someone contacts Nikita. Even though the action is what attracts many to La Femme Nikita, its heavy psychedelic overtones are what transform it into a terrific film. Additionally, the main characters are intriguingly flawed, at times even weird.

By the time she meets up with her fiancé-to-be and is called to perform various undercover tasks eliminating subjects as part of her ongoing missions, you feel for the girl and her tough choices. Various scenes are memorable in this film, but one of my favorite actors is Jean Reno as “The Cleaner,” who shows up and saves the day.

Just when we are starting to think that Nikita’s domestic-hit-woman gig looks a little too easy, Besson pulls the rug out from under us. One of the missions goes haywire, and suddenly what had seemed like a slam-dunk mission is shown to have actual consequences. It's a clever gambit, and Besson stages it beautifully. Anne Parillaud, Besson’s wife at the time, gives the film a sullen, acrimonious seriousness often missing in American films of this same type (i.e. Killing Zoe, The Long Kiss Good Night). Nikita was remade in Hollywood as Point of No Return with Bridget Fonda and in Hong Kong as Black Cat; the film also spawned an American cable-television show called Le Femme Nikita.

Unfortunately , there aren’t enough cool action movies starring women out there, but if I had to choose from the handful of flicks that are floating about (and no, I don’t consider Tomb Raider “cool” or “good” for that matter), La Femme Nikita, Alien, and Thelma & Louise would definitely ride high atop that list. Next to Sigourney Weaver and Angelina Jolie, Anne Parillaud is one of the greatest action hero actresses of all time!

This movie is successful on so many levels. It has action scenes for the genre lovers, its narrative, for those who are intrigued by underground covert organizations, its writing and directing, both of which stamp the film with a real sense of authenticity and…its romance? Yep, you heard me right, not only does this film manage to balance some wicked shoot-out scenes, an appealing super-spy lead actress, and plenty of bang for your buck, but it also manages to showcase a believable love story at the same time. And that’s only one of the many things that kept me interested every time I watch this movie.

*****************************************************************************************************

Cross-Cultural Film

***************************************************************************

Italy: Life is Beautiful

The film has two parts to it. In the first part Benigni, who also co-wrote the script with Vincenzo Cerami, plays Guido, a waiter working for his uncle who owns a hotel in Italy. He keeps bumping (literally) into his principessa Dora (Nicoletta Braschi). By staging an elaborate (and humourous!) series of events which make it appear as if the Virgin Mary herself is cooperating with him, Guido rescues Dora from marrying the stodgy town clerk. Life appears to be going fairly well for Guido even though Mussolini has just signed a pact with Hitler to implement his Nazi policies with regards to Jews. Flash forward five years later and we see Guido owning a bookstore he manages with his wife and son Giosué. It's almost the end of World War II, but that makes the position of Jewish-Italians all the more precipitous. One day, the Germans come to take away Guido and his son. His wife, not being Jewish, chooses to go along.

Right from the start, Guido takes a huge risk by treating the whole exercise as a joke. He explains to his son that they've just bought tickets to take part in a contest to win a tank (not a toy one, but a real one, the thought of which lights up Giosué's eyes) and proceeds to concoct an imaginative and humorous explanation for the happenings around, and to, them in the German concentration camp.

All of the things Guido asks Giosué to do are in the interest of saving Giosué. However, given Guido's personality depicted in the first half of the film, I don't think he could've acted differently even if he wanted to. While the first part of the movie illustrates Benigni's talents as a slapstick comedian, some of the best humor is in the German camp. Here, Guido is not only funny to his son (and the audience), but he must also eke out humor in situations where people's lives are at stake. We see Guido making a joke out of a German officer's instructions to the prisoners---a situation where a misunderstanding on the part of the prisoner could lead to their deaths.

When I first heard about the Italian movie Life Is Beautiful ("La Vita e Bella"), I was shocked to discover that it was a comedy about the Holocaust. The articles that appeared in the papers bespoke of many that found even the concept of the Holocaust portrayed as a comedy to be offensive. Others believed that it belittled the experiences of the Holocaust by inferring that the horrors could be ignored by a simple game. I, too, thought, how could a comedy about the Holocaust possibly be done well? What a fine line the director (Roberto Benigni) was walking when portraying such a horrible subject as a comedy.

Life is Beautiful caused more than a little controversy when it was released: any attempt to make comedy out of the Holocaust is going to inspire strong reactions from critics and audience members. Love it or loathe it, Life is Beautiful inarguably made an international star out of Italian comedian Roberto Benigni, who wrote, directed, and starred in it. One of his country's most celebrated comedians, Benigni was previously known for his work in numerous Italian comedies, as well as Johnny Stecchino and Jim Jarmusch’s Down By Law and Night on Earth. Life is Beautiful's Grand Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, followed by Benigni's Best Actor Oscar and acceptance speech (in exuberant, skillfully broken English), made Benigni possibly Italy's most famous export since the Fiat. Although some viewers found the film's second half, set almost entirely in a concentration camp, to be well-meaning but misguided, the film's first half is indisputably enjoyable.

Revolving around the courtship of an aristocratic lady nicknamed the Principessa by Benigni's Guido, it makes a refreshing, elegantly hilarious love story. Somewhat ironically, the film's wittiest and most accurate commentary on fascism and religious oppression is contained here, rather than in the concentration camp setting. Benigni’s comedy here becomes a tool for side-splitting yet razor-sharp criticism, and this first section powerfully establishes the reality of everyday life disrupted by the war.

********************************************************************************************************

South Africa: Tsosti

An amoral teenager develops an unexpected paternal side in this powerful drama from South Africa. Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) is the street name used by a young Johannesburg delinquent who has taken to a life of crime in order to support himself. Tsotsi comes from a blighted upbringing -- his mother died slowly from AIDS-related illnesses, and his father was torturously abusive -- and he has developed a talent for violence borne of necessity as well as taking strange pleasure in hurting other people. One evening, Tsotsi shoots a woman while stealing her car, and only later discovers that her infant son is in the back seat. Uncertain of what to do with the baby, Tsotsi takes the boy home and tries to care for it -- going so far as to force Miriam (Terry Pheto), a single mother living nearby, to nurse the baby. With time, Tsotsi learns the basics of child care, and the presence of the baby awakens a sense of humanity in him that life on the street had stripped away.

When we first meet the South African teen known as Tsotsi (not an actual name but a generalizing slang term meaning “thug” or “gangster”), he is about to make the leap from simple hooligan to something far more sinister; yet as the story unfolds, the viewer gradually discovers that his tale is a bit more complicated than it first appears.

What’s so powerful about this film is that we do see the change in Tsotsi. Maybe we don’t see the complete change, and maybe this change just won’t take. But we see the start of it. And while his deeds in his past are extremely unforgivable, we see how a spiraling series of events can start the wheels of change.

With Tsotsi, writer/director Gavin Hood has achieved the rare feat of presenting a character whose quick temper and cold exterior make him easy to fear in the opening scenes, and gradually providing the audience with the backstory needed to understand that those components of his personality are but a small part of a much larger picture painted by the tragedy and sadness of his harsh childhood. We are all a product of our youth, and Tsotsi's youth was one of death, poverty, and abuse.

One of the biggest scenes in the film that really got to me, emotionally, was when Tsotsi follows Morris, the old beggar in the wheelchair, into a dirty alley alone at night. Morris thinks he’s trying to rob him, so he defends himself, but he can’t hide his vulnerability. Tsotsi follows him because Morris spat at him and insulted him after Tsotsi tripped over him, which Morris obviously took out of disrespect. Once the old man starts to cry, you can feel what he feels emotionally. It is more saddening when Tsosti tells Morris his story about the dog getting kicked twice. I think Morris did that only because he wanted to prove that he can still be a strong man, even though he is now a cripple. Even though he was a man in a wheelchair, he still wanted to be that man who worked in the gold mines until he became permanently crippled when a beam fell on his legs. I didn’t like that Tsosti kicked the box full of money, and left the old man, without picking it up for him!

This film won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, and it is well deserved. Though the story is at times predictable and occasionally crosses the line into sappy sentimentality, effective performances and believable motivations allow the viewer to become involved in the proceedings in a manner that lends the film a convincing element of believability. On the visual front, cinematographer Lance Gewer's crisp cinematography serves well to highlight the stark contrast between the decayed shantytown in which Tsotsi survives and the modern comforts of the nearby city where there still remains a glimmer of hope.

******************************************************************************************************************

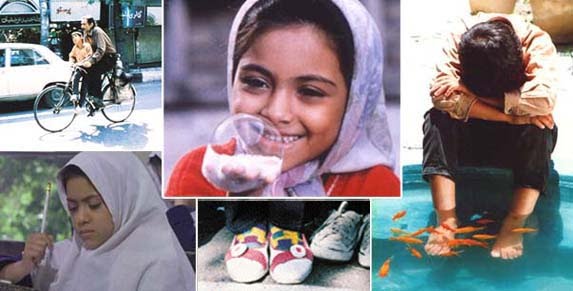

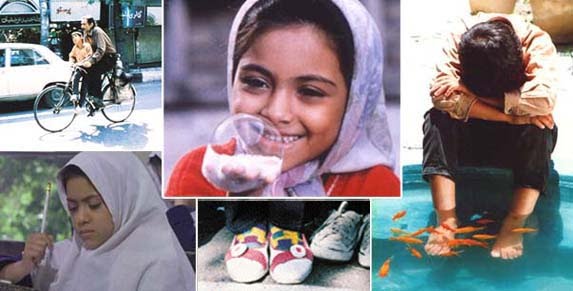

Iran: Children of Heaven

Director Majid Majidi's touching children's film tells a story of innocence, heartbreak, and determination so well that it may in time be regarded as a classic of the genre.

Set in Majidi’s native Tehran, Children of Heaven is the story of a brother and sister, Ali and Zahra. The film opens with Ali (Mohammad Amir Naji) sitting beside a shoemaker who is repairing a tiny pair of worn shoes. Ali then carries the shoes to a fruit market, leaving them outside the door while he searches through the discarded cartons the vendor has pointed to. It’s not an irresponsible act; Ali is simply being practical. It's a small shop. He must pick through the fruit, and he can't do that while he's holding the bag containing the shoes. A man comes along with a cart and asks the vendor if he can haul off the empty cartons. The vendor nods, and the man picks up everything outside the shop, including the bag containing the shoes. We soon learn that the shoes belong to Zahra (Mir Farrokh Hashemian), Ali’s sister. The family, whose poverty makes it necessary for the children to bear many adult responsibilities, is behind on the rent for their tiny, one-room apartment. The children's father, who is employed in an office, would have to borrow to buy Zahra another pair of shoes, but without the shoes Zahra can’t go to school. So the children come up with their own solution: Since Ali and Zahra go to school at different times, they decide to share Ali’s equally worn sneakers. The entire film is about that bargain, and the compromises it requires of the children.

After much pondering, Ali devises a plan to give his sneakers to Zahra so that she may continue her studies; this results in Ali being late for school while he waits for Zahra to come back and give him the shoes. At last they manage to reach a plan to use these shoes one after the other. The whole movie revolves around this inexpensive footwear which is not of much significance to countless others, but it is to these two children. To Zahra, it was disgraceful to wear sneakers in a girl’s school where others like her were wearing fancy colorful shoes. Her brother Ali understands the naive feelings of his sister and promises to bring new shoes for her someday.

Movies about children for adult audiences are rarely commercial successes. Narrative films such as Mike Newell’s Into the West and John Sayles’ The Secret of Roan Inish, and experimental ones like the Australian film, The Quiet Room, by writer/director Rolf DeHeer, are only a few recent examples. That’s because, for all our expressed concern about the lives of children, we still fail to accept the fact that they have spiritual lives not very different from our own, and that they suffer as profoundly and as deeply as we do. More examples would be Steven Spielberg’s movies made for children and families, like ET: The Extra-Terrestrial, The Goonies, and Hook.

Majid Majidi’s Children of Heaven has recently become Iran’s first-ever Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Language Film; it is both an inspiring and a dispiriting event. On the one hand, Iran has been turning out a startling number of accomplished and striking films for the past decade, and the past five years especially. To see the country recognized by the Academy is a cause for great joy among those who have been swept up by the country's film output.

*********************************************************************************************************

.jpg)

Israel: Walk On Water

An Israeli agent with a license to kill is thrown off his game by two people who challenge his deeply held beliefs in this drama. Eyal (Lior Ashkenazi) is an agent with Mossad, the Israeli intelligence and security force. A man capable of making snap moral judgments but unwilling to reveal his emotions, Eyal has been burying himself in his often bloody work since the death of his wife. Eyal's latest assignment is to try to learn the whereabouts of a Nazi war criminal; as it happens, his granddaughter Pia (Carolina Peters) is in Israel spending time on a kibbutz, and when he learns that her brother Axel (Knut Berger) is coming to visit her, Eyal goes undercover as a tour guide in order to get to know them without arousing suspicion. Eyal finds himself taken with Pia, who displays a warmth and openness he's never expected to find in a German. At the same time, Eyal discovers Axel is gay and doesn't care who knows about it, and as Eyal gets to know him he finds himself torn between his genuine fondness for Axel and his long-standing homophobia. Walk on Water was directed by Eyton Fox, who earned international acclaim for his story about two gay men in the Israeli army, Yossi & Jagger.

After the suicide of his wife, conservative Mossad agent Eyal is put on “light duties” — confirming the existence of a Nazi in hiding who may be about to surface. The way in is through his grandchildren, and posing as a tour guide for grandson Axel as he visits granddaughter Pia. Eyal gradually warms to the new generation of Germans — even when he belatedly realizes that Axel is openly gay.

Irony abounds in Walk on Water. Eyal's distrust of all things German was ingrained in him by his survivor mother. He is challenged directly by Axel, who two generations after Eyal's own grandfather sent an entire community to the death camps, is not only openly gay (making him a potential target of Neonazis), but also as disgusted as Eyal himself by the ideology of the Third Reich (and by his own grandfather).

The uniformly excellent performances feel real and familiar, while the handheld camerawork only occasionally becomes intrusive. There’s also a slightly clunky fight sequence, but it’s brief and does not detract from the film. The themes of revenge and redemption feel justified, and whether you find the military coda appropriately optimistic or just plain convenient will be a matter of taste. Despite the very optimistic ending, this film is moving, interesting and compelling viewing with superb performances.

**********************************************************************************************************

Brazil: Central Station

The film tells a familiar story — crusty oldster finds humanity through a needy child — in bracingly unsentimental fashion. Brazilian-legend actress, Fernanda Montenegro, plays Dora, a bitter retired schoolteacher who earns money by writing letters for illiterate patrons in a Rio train station. The fact that she never bothers to mail the letters is a function of her chilly disregard for the human race.

The agent of her redemption is a little boy named Josue, played with miraculous emotional honesty by Vinicius de Oliveira, whom director Walter Salles found shining shoes in a Brazilian train station.

After his mother is killed, Josue badgers Dora into taking him to find his father in a distant province — but only after she has very nearly abandoned him to an unknown fate in a city where youthful thieves are gunned down by private security guards. Their trip together is an ordeal and an adventure, punctuated by Dora’s efforts to unload the boy. But the boy refuses to let her run away.

Together they encounter outlaws, pilgrims, and a kind-hearted Christian truck driver who seems, briefly, to be Dora’s savior. Eventually, they find their way to something like home, in the heart of a remote world neither entirely understands.

All the same, the film is affecting and pointedly unsentimental in its portrayal of the often grudging relationship between the gruff, callused Dora and Josue, who only abstractly grasps the importance of the search they've undertaken and doesn’t realize, as the audience does, that its result will determine whether he will join the ranks of the country’s millions of street kids or manage to get a shot in life through a family connection.

While the duo never find Josue’s father (whom Dora keeps referring to as a drunkard and abuser), they eventually do find his two half-brothers, idealistic young men who ultimately end up raising the young boy. They also discover that Josue’s mother was really the love of his father’s life and that he had traveled to Rio to find her - not the bad man Dora had painted after all. The final image (and natural conclusion) is a heartbreaker, yet we know these two people we’ve come to know so well, have ended up so much better than they had begun.

I wasn’t in the mood for this film, but it got to me anyway. The main reason is Montenegro, who is kind of a Latin Jessica Tandy. The film kicks in hard at the point where Dora is broke and suddenly very desperate. The hook here is the letters she writes for others. As people read or dictate them, they reveal themselves. Even when, late in the movie Dora reads aloud from someone else’s letter, she reveals her own feelings. The letters accentuate a theme of loneliness and the inability to communicate. Dora survives by helping others speak, but fails to deliver the message. She redeems herself by attempting to personally deliver the letter and the boy to his father. On the way, she crosses both physical and spiritual landscapes to reach others. The letter, child, and now spiritual mother complete the journey by meeting another letter. Dora then writes her own to mark her return from one frontier to leave her heart at the other end.

Long one of Brazil’s leading stage and screen actresses, Montenegro carries the film superbly with her portrait of gritty strength being worn down to a state of tattered vulnerability, while newcomer de Oliveira, a shoeshine boy who won the role over 1,500 other aspirants, is engagingly natural and happily doesn’t beg for viewer sympathy. Director Walter Salles presents the side of Rio which most tourists don't see - it's ugly, painted in sallow colors, crowded and harsh - certainly no place for young children (a teenage thief is shot on the train tracks for stealing a cheap radio from a junky subway stall). When we meet Dora, she seems a natural part of this unlovely landscape. She's not pretty, either physically or spiritually, her only wish being to make enough money for her petty trifles like cheap booze. Montenegra is perfect in this role and was Oscar-nominated for Best Actress in 1998. While she did not win, I thought she should have.

On a precise but restrained symbolic level, Central Station speaks cautiously in a hopeful manner about the possibilities for Brazil’s future. It suggesting that the deep scars left by the social ills of the recent past might somehow be survived and surmounted by a creative union of the old and the new Brazils.

***********************************************************************************************************

Mexico: Amores Perros

The film is constructed from three distinct stories linked by a car accident that brings the characters briefly together. Octavio is sharing an apartment with his brother, which leads to a serious problem when he falls in love with Susanna, his sister-in-law. Octavio and Susanna want to run away together, but Octavio has no money. He does, however, know a man who stages dog fights, and he volunteers his dog Cofi for the next round of fights. Cofi bravely rises to the occasion, but the dog's success in the ring leads to a violent altercation. Elsewhere, Daniel, a successful publishing magnate, leaves his family to take up with a beautiful model, Valeria. Valeria, however, soon loses a leg in an auto accident, and as Daniel tends to her needs, her tiny pet dog gets trapped under the floorboards of their apartment. And finally, El Chivo is an elderly homeless man who is trying to contact his daughter, whom he hasn't seen in years. Desperate for money, El Chivo is hired by a businessman to assassinate his partner; however, as he's following his target, he’s interrupted by an auto accident, from which Octavio and his injured dog stagger in search of help.

Translated very loosely as Love’s a Bitch, a phrase that’s invoked both literally and figuratively, Amores Perros opens with a spectacularly jarring car crash and flips back and forth to show how the victims and onlookers collided at the scene.

What a shock, then, to see Amores Perros and discover that Mexico City is actually... a hotbed of violence and vice! Boasting the highest canine mortality rate since Verhoeven’s Hollow Man, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s thriller opens with a cautionary note that no animals were harmed in the movie’s making--no doubt to allay fears that life is cheap south of the border. But violence against animals on film seems a lot more shocking and taboo than violence against humans—an issue this trio of intertwined stories exploits to disturbing and frequently dazzling effect.

And all of that makes it sound pretty depressing as well, so let me digress by saying that the film takes a lot of fun and energy in telling its stories without losing the edge. Indeed, some of the best moments in the film play like the soap operas where Selma Hayek received her start. Every character has a love lost or a love to strive for. Love is a bitch, the filmmaker’s tell us, but it is also a force that can drive people beyond things like dreams and plans. “Plans are what we tell God, so He can have a good laugh,” one character says at a pivotal moment. Now, isn’t that an absurdly tragic line. And Amores Perros is one of those few films that can exist in all the different worlds of these characters, tragic and absurd.

The movie bears more than a passing resemblance to Pulp Fiction. It has three major stories, each of them beginning with a title card. The stories weave and wind through each other without adhering strictly to straightforward chronology. The feel of the movie is gritty, at times suspenseful, at times frantic, and often violent and bloody. Its subjects are low lives, people who would do terrible things for money and love, or people who do terrible things with the money they have. What it doesn't have that Pulp Fiction does is the humor that made Pulp Fiction's proceedings feel like a black comedy. Amores Perros is all serious, always observing the human condition with a sad, pitying eye.

I pretty much hated this film! It was way too long of a feature to watch in a classroom, and it was way too graphic for me to watch. I’m a dog lover myself, and I cannot stand watching scenes of dogs killing each other for the pleasure of humans, who mistreat their dogs and use dog fighting as a fun sport. There were a lot of scenes in which the dogs were fighting and actually show the violence of the sport. I even looked away from the screen a couple of times, but that was worse! Because all I heard was the growling and yelping of the dogs! In the second story, about the crippled model, I was feeling even sorrier for the dog, which fell into the hole of the apartment floor. Throughout that entire story line, the dog was stuck under the floor of the apartment, which was full of rats. I also couldn’t stand the sight of the scene where the dog fighter killed all of the dogs and puppies in the assassin’s home. One positive note about this film: If you are a dog lover, this film will make you love your dog even more and feel sorry for all the house dogs and stray dogs, who could be victims of a vicious dog fighting ring (Talking to you, Michael Vick!)

*****************************************************************************************************************

India: Bombay

Bombay ends on a hopeful note, but not before etching a series of wrenching images in the minds of viewers. Director Mani Rathnam has shown great courage in making this picture (bombs were thrown at his house after it opened in India), which speaks with a voice that many will not wish to hear. Bombay recalls how forceful a motion picture can be. It also reminds us of the maxim that those who don't learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Hopefully, some day, humankind will understand the lesson that Rathnam is teaching here.

Another thing we are shown, and this is quite a common message in the Indian cinema lately, is how the riots are the result of the politicians’/religious leaders’ vicious manipulation of the people's minds. Although the political message of the film is very plain, to the point of being of pamphlet quality, and the emotional dirty tricks are felt as so many blows below the belt, it takes Bollywood to make from all this tricky material a gripping story that has the audience watching on, with a lump on their throat, for three hours.

You can also find more levels than just the purely superficial in the movie: there is always the symbolism, so dearly loved by Indian cinema, as in the case of the twins and their fate. And there are some subtler messages: when one of the boys gets lost and is in danger of being trampled to death by a terrified mob, he is rescued by a eunuch. And it is this most despised and marginal of members of society who, while tending to the boy’s wounds and feeding him, finally explains to the boy what religion is, and what is the difference between a Muslim and a Hindu.

Mani Rathnam shows how Bombay struggles to find a narrative that can reconcile communal differences. She looks in detail at the way official censors tried to change the film under the influence of powerful figures in both the Muslim and the Hindu communities. In going on to analyze the aesthetics of Bombay, she shows how themes of social and gender difference are rendered through performance, choreography, song and cinematography.

Within film and television or within modern novels and books have had various star-crossed lovers labeled as notable and “unforgettable” love stories. Obviously, the greatest star-crossed lovers’ story ever told is William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the play that has become a popular icon, in terms of forbidden love stories, and inspired a movie like Bombay into a beautiful story about love. I consider Buffy Summers and Angel from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to be one of the genre’s most tragic and notable star-crossed pairings. Other examples like, Cole Turner and Phoebe Halliwell from Charmed, Nikita and Marco from La Femme Nikita, Kara Thrace and Lee Adama from Battlestar Galactica, and Clark Kent and Lana Lang from Smallville are other star-crossed couples from that particular genre. More star-crossed, couples such as, Jack Dawson and Rose DeWitt Bukater from Titanic, Landon Carter and Jamie Sullivan from A Walk to Remember, Anakin Skywalker and Padmé Amidala from the Star Wars saga, and Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist from Brokeback Mountain. Also, more recently, Bella Swanson and Edward Cullen from Twilight and New Moon, and Jake and Neytiri from Avatar have been included.

The biggest significance of this film is the music and musical numbers. The original soundtrack features the music score and six songs from the movie are composed by A. R. Rahman, with lyrics in the Tamil language by Vairamuthu. The soundtrack was also dubbed into Hindi and Telegu. You would know Rahman as the composer who won two Oscars for composing the music and songs from the 2009 Academy Award winning-film, Slumdog Millionaire. As usual with Bollywood films, there are musical numbers, but in this case we don’t have any major star of India, although the main actors are great (Manisha Koirala is especially charming in the style of Audrey Hepburn); but you have to watch out for the support actors: whenever the two fathers-in-law (one of them a very pious Muslim, the other a very pious Hindu...always having comical clashes) are in a scene the screen rocks! This film is not your average everyday American Broadway musical! The music and the songs were very catchy, fun to listen to, but you could easily tell that the actors in the movie were lip-syncing the songs through every single number.

Though Bombay may not tick your intellectual brain... It surely engages your heart into an emotional journey. Mani Ratnam is really successful at bringing in the perfect Indian middle-class life with stunning cinematography and flawless acting. For those you want to see a nice movie filled with a good story line, not heavy on emotion and above all a scintillating music this is a good movie to see.

********************************************************************************************************************

Taiwan: Eat Drink Man Woman

Eat Drink Man Woman, derived from an original script by James Schamus, Hui-Ling Wang, and the film's director, Ang Lee, is simple, light, and hard to hold anything against. The main character, Mr. Chu (Sihung Lung), is a consummate chef whose sense of taste has begun to dull as he enters old age. Also growing less secure are his relationships to his three, very different daughters—as though three sisters in the same movie ever have anything in common. In fact, part of what gives Eat Drink Man Woman its appeal, at least for an American viewer like myself, is that the unfamiliar pleasures of the scrumptious fine food and the Taipei setting are comfortably nestled within a tried-and-true, instantly recognizable plotline. A major theme of the movie is that romantic relationships give life meaning and are necessities of life (such as eating and drinking).

This film is set in Taipei, and is spoken in Mandarin. The important theme to this story is hinted at when the father repeats to his daughters that he has lost his taste a long time ago. The audience later knows that he was referring more to his taste for life rather than his physical inability to distinguish flavors. This lack of appreciation for life comes with age as well as his loneliness from accepting the inevitable -- that his daughters are going to leave him alone someday. There are so many subtleties this film is able to capture about not only the Chinese culture, but living with women in general. Each daughter's relationship reflects the uniqueness of individuals. Eat Drink Man Woman is full of humor, wisdom, and grace.

I love to watch this film. I suggest that you eat a full meal before you watch this motion picture. The savory dishes created by the father who is a chef in a major hotel in Taipei, Taiwan makes your mouth water and your glands salivate. I want to be in this film and enjoy a meal with the master chef. Ang Lee is a superb director who has captured family dynamics in modern day China. Whether you are a China expert or just starting to learn about the culture, this is a great way to experience the internal life of an atypical Chinese family. The story will captivate you; the ending will be a surprise to you. This film is definitely more of a chick flick than anything else. It's like a Taiwanese Sex and the City, even with the use of the theme music from the film/television show. This is truly a movie with an ensemble cast. There are four different stories that surround each of the four main characters. This film has comedy, drama, and romance (That's why this movie is a chick flick!) For everybody and for me, especially because I am a good cook and love food, there was the constant gourmet dishes being cooked, served, and consumed!

****************************************************************************************************************

France: La Femme Nikita

Some of the greatest French movies have been remade for US audiences and no one knows about it. French Director Luc Besson made one of his best with this movie. Because I don’t speak French, it is better for me to watch subtitles than listen to terrible English dubbing. Fans of the Bourne series will probably enjoy this film. After the first 20 minutes, I thought the film was kind of boring. I had no idea where the plot was going, but soon after, La Femme Nikita began to pick up pace and developed into a film I really enjoyed. The movie creates an interesting dialog between violence and the woman's growing reaction to the violence she has to commit. An interesting love twist further develops the character and that’s what the movie is about.

More importantly, and as some reviewers have noted, Nikita combines thrilling action and tension (without the expensive FX) with a very touching sense of humanity. Here you have a junkie social reject turned into a proper, well-behaved, yet deadly government agent. It’s interesting how the government selected someone who was about to go to jail, rather than picking from a horde of eager, patriotic young recruits who would beg to do the job. The government’s mistake is that they assume this reject is just effectively a machine and has no redeeming human qualities. As the film progresses, you see that Nikita yearns for intimacy and love - it's what makes her vulnerable and it's also probably what makes her so good at the job.

A gang of junkies breaks into a drugstore, but the police arrive and corner them in. All are killed, with the exception of a young woman (Anne Parillaud). She is arrested and immediately sentenced to death. Before the sentence is carried out, however, the government gives the woman a second chance – they promise to let her live if she agrees to work for them. She does and her death is faked. The woman is instantly locked in a secret facility where she is trained to become an assassin. Three years later, the woman is released with a new identity - Nikita. She is told that when the government needs her services someone will contact her. A charming store clerk, Marco (Jean-Hugues Anglade), falls for Nikita. The two become friends and then lovers. Nikita likes her new life and decides that Marco should never be told about her past. Then, someone contacts Nikita. Even though the action is what attracts many to La Femme Nikita, its heavy psychedelic overtones are what transform it into a terrific film. Additionally, the main characters are intriguingly flawed, at times even weird.

By the time she meets up with her fiancé-to-be and is called to perform various undercover tasks eliminating subjects as part of her ongoing missions, you feel for the girl and her tough choices. Various scenes are memorable in this film, but one of my favorite actors is Jean Reno as “The Cleaner,” who shows up and saves the day.

Just when we are starting to think that Nikita’s domestic-hit-woman gig looks a little too easy, Besson pulls the rug out from under us. One of the missions goes haywire, and suddenly what had seemed like a slam-dunk mission is shown to have actual consequences. It's a clever gambit, and Besson stages it beautifully. Anne Parillaud, Besson’s wife at the time, gives the film a sullen, acrimonious seriousness often missing in American films of this same type (i.e. Killing Zoe, The Long Kiss Good Night). Nikita was remade in Hollywood as Point of No Return with Bridget Fonda and in Hong Kong as Black Cat; the film also spawned an American cable-television show called Le Femme Nikita.

Unfortunately , there aren’t enough cool action movies starring women out there, but if I had to choose from the handful of flicks that are floating about (and no, I don’t consider Tomb Raider “cool” or “good” for that matter), La Femme Nikita, Alien, and Thelma & Louise would definitely ride high atop that list. Next to Sigourney Weaver and Angelina Jolie, Anne Parillaud is one of the greatest action hero actresses of all time!

This movie is successful on so many levels. It has action scenes for the genre lovers, its narrative, for those who are intrigued by underground covert organizations, its writing and directing, both of which stamp the film with a real sense of authenticity and…its romance? Yep, you heard me right, not only does this film manage to balance some wicked shoot-out scenes, an appealing super-spy lead actress, and plenty of bang for your buck, but it also manages to showcase a believable love story at the same time. And that’s only one of the many things that kept me interested every time I watch this movie.

*****************************************************************************************************

Followers

About Me

- William E. Struthers

- Hola!! My name is William Struthers, and I am Senior at Kean University, Majoring in Film & Media!!!